|

HDF5 Last Updated on 2026-02-04

The HDF5 Field Guide

|

|

HDF5 Last Updated on 2026-02-04

The HDF5 Field Guide

|

Navigate back: Main / HDF5 User Guide / Additional Resources

Datasets in HDF5 not only provide a convenient, structured, and self-describing way to store data, but are also designed to do so with good performance. In order to maximize performance, the HDF5 library provides ways to specify how the data is stored on disk, how it is accessed, and how it should be held in memory.

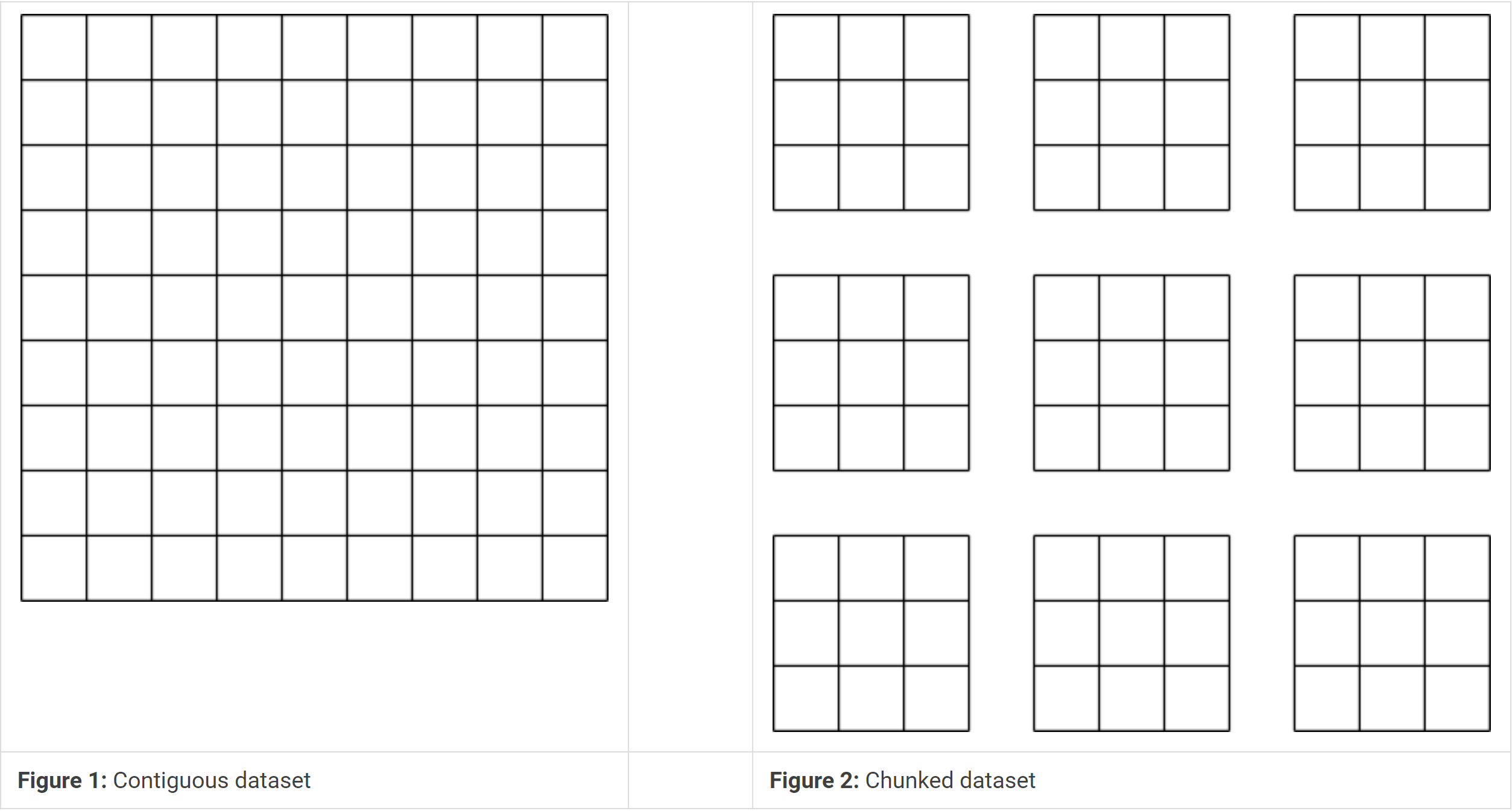

Datasets in HDF5 can represent arrays with any number of dimensions (up to 32). However, in the file this dataset must be stored as part of the 1-dimensional stream of data that is the low-level file. The way in which the multidimensional dataset is mapped to the serial file is called the layout. The most obvious way to accomplish this is to simply flatten the dataset in a way similar to how arrays are stored in memory, serializing the entire dataset into a monolithic block on disk, which maps directly to a memory buffer the size of the dataset. This is called a contiguous layout.

An alternative to the contiguous layout is the chunked layout. Whereas contiguous datasets are stored in a single block in the file, chunked datasets are split into multiple chunks which are all stored separately in the file. The chunks can be stored in any order and any position within the HDF5 file. Chunks can then be read and written individually, improving performance when operating on a subset of the dataset.

The API functions used to read and write chunked datasets are exactly the same functions used to read and write contiguous datasets. The only difference is a single call to set up the layout on a property list before the dataset is created. In this way, a program can switch between using chunked and contiguous datasets by simply altering that call. Example 1, below, creates a dataset with a size of 12x12 and a chunk size of 4x4. The example could be changed to create a contiguous dataset instead by simply commenting out the call to H5Pset_chunk and changing dcpl_id in the H5Dcreate call to H5P_DEFAULT.

Example 1: Creating a chunked dataset

The chunks of a chunked dataset are split along logical boundaries in the dataset's representation as an array, not along boundaries in the serialized form. Suppose a dataset has a chunk size of 2x2. In this case, the first chunk would go from (0,0) to (2,2), the second from (0,2) to (2,4), and so on. By selecting the chunk size carefully, it is possible to fine tune I/O to maximize performance for any access pattern. Chunking is also required to use advanced features such as compression and dataset resizing.

|

To understand the effects of chunking on I/O performance it is necessary to understand the order in which data is actually stored on disk. When using the C interface, data elements are stored in "row-major" order, meaning that, for a 2- dimensional dataset, rows of data are stored in-order on the disk. This is equivalent to the storage order of C arrays in memory.

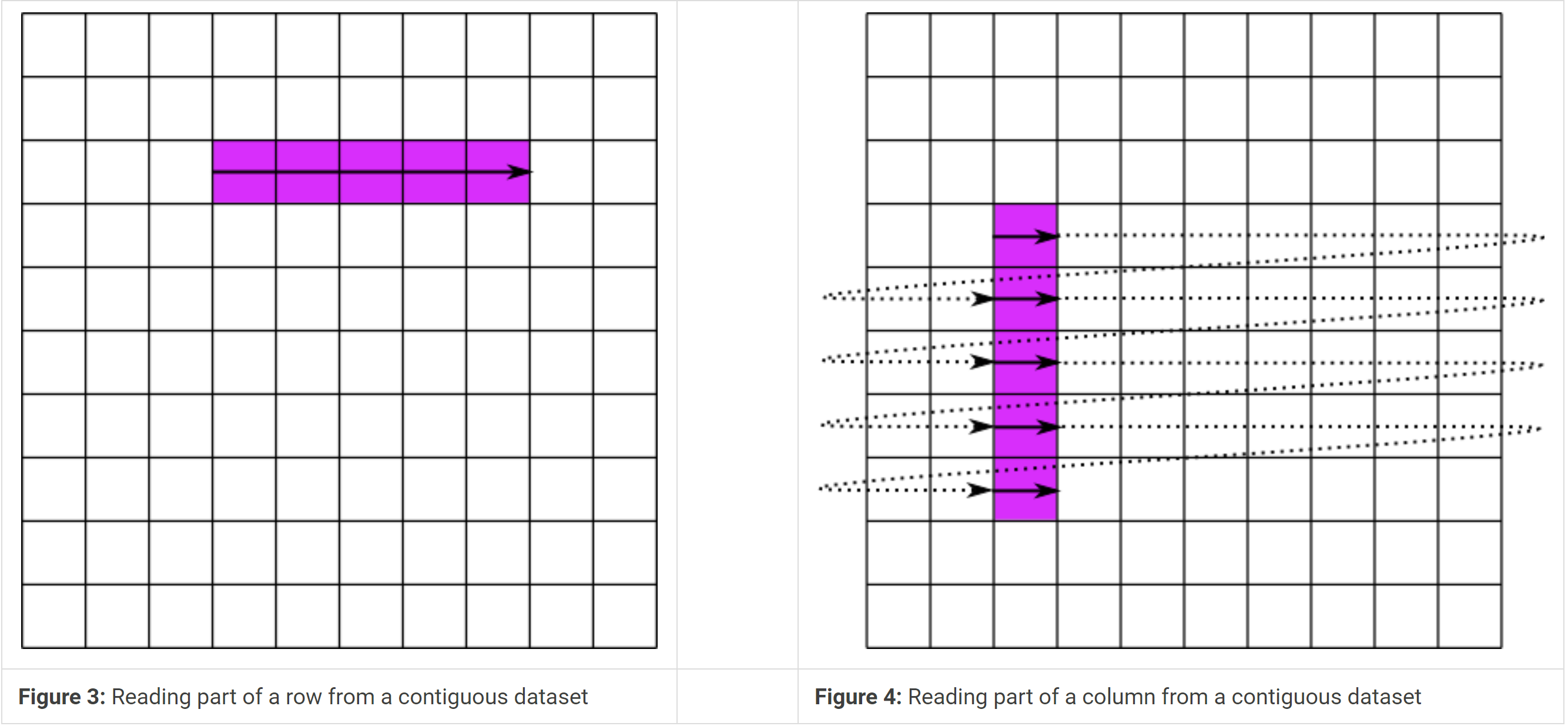

Suppose we have a 10x10 contiguous dataset B. The first element stored on disk is B[0][0], the second B[0][1], the eleventh B[1][0], and so on. If we want to read the elements from B[2][3] to B[2][7], we have to read the elements in the 24th, 25th, 26th, 27th, and 28th positions. Since all of these positions are contiguous, or next to each other, this can be done in a single read operation: read 5 elements starting at the 24th position. This operation is illustrated in figure 3: the pink cells represent elements to be read and the solid line represents a read operation. Now suppose we want to read the elements in the column from B[3][2] to B[7][2]. In this case we must read the elements in the 33rd, 43rd, 53rd, 63rd, and 73rd positions. Since these positions are not contiguous, this must be done in 5 separate read operations. This operation is illustrated in figure 4: the solid lines again represent read operations, and the dotted lines represent seek operations. An alternative would be to perform a single large read operation, in this case 41 elements starting at the 33rd position. This is called a sieve buffer and is supported by HDF5 for contiguous datasets, but not for chunked datasets. By setting the chunk sizes correctly, it is possible to greatly exceed the performance of the sieve buffer scheme.

|

Likewise, in higher dimensions, the last dimension specified is the fastest changing on disk. So if we have a four dimensional dataset A, then the first element on disk would be A[0][0][0][0], the second A[0][0][0][1], the third A[0][0][0][2], and so on.

The issues outlined above regarding data storage order help to illustrate one of the major benefits of dataset chunking, its ability to improve the performance of partial I/O. Partial I/O is an I/O operation (read or write) which operates on only one part of the dataset. To maximize the performance of partial I/O, the data elements selected for I/O must be contiguous on disk. As we saw above, with a contiguous dataset, this means that the selection must always equal the extent in all but the slowest changing dimension, unless the selection in the slowest changing dimension is a single element. With a 2-d dataset in C, this means that the selection must be as wide as the entire dataset unless only a single row is selected. With a 3-d dataset, this means that the selection must be as wide and as deep as the entire dataset, unless only a single row is selected, in which case it must still be as deep as the entire dataset, unless only a single column is also selected.

Chunking allows the user to modify the conditions for maximum performance by changing the regions in the dataset which are contiguous. For example, reading a 20x20 selection in a contiguous dataset with a width greater than 20 would require 20 separate and non-contiguous read operations. If the same operation were performed on a dataset that was created with a chunk size of 20x20, the operation would require only a single read operation. In general, if your selections are always the same size (or multiples of the same size), and start at multiples of that size, then the chunk size should be set to the selection size, or an integer divisor of it. This recommendation is subject to the guidelines in the pitfalls section; specifically, it should not be too small or too large.

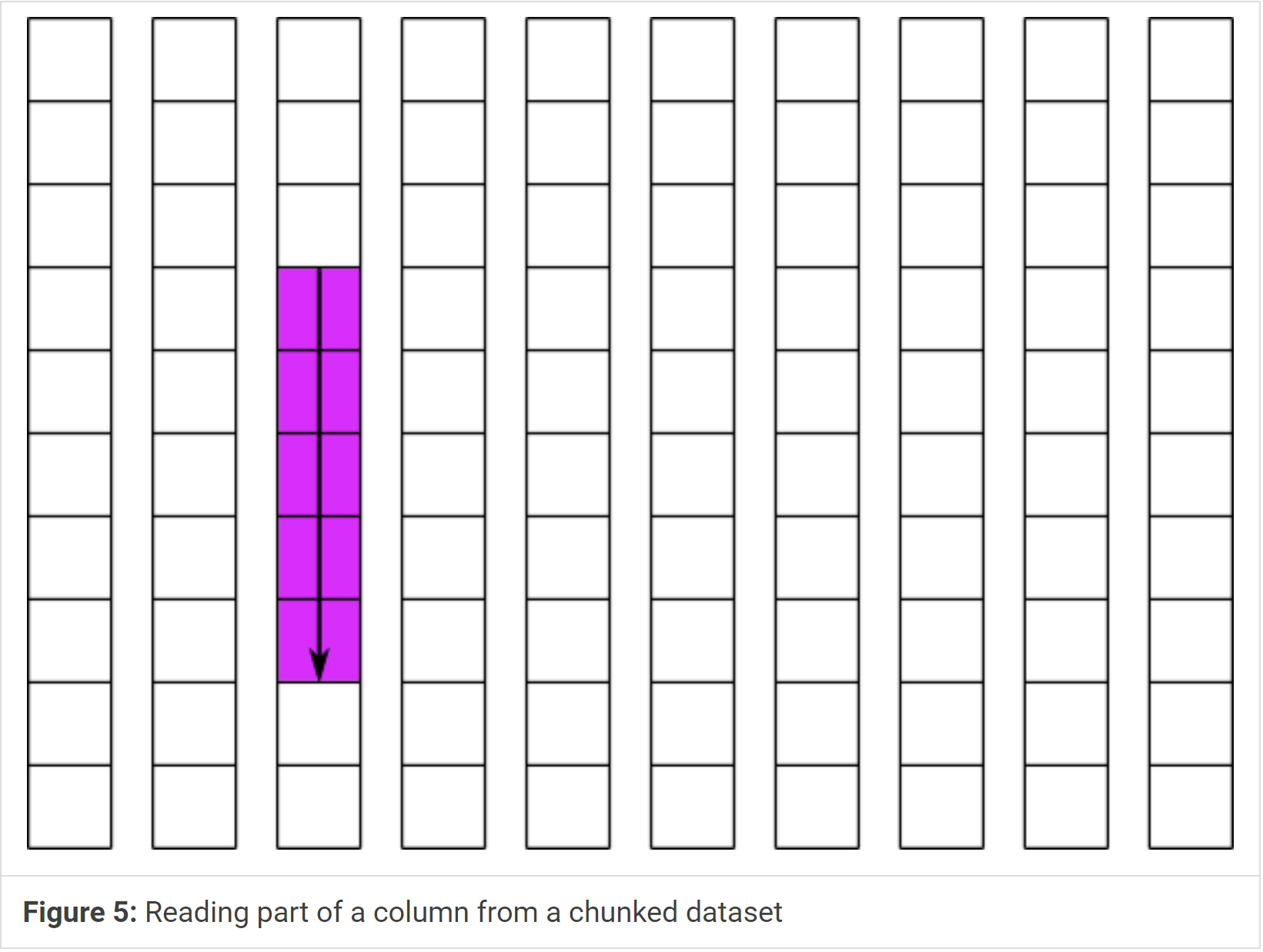

Using this strategy, we can greatly improve the performance of the operation shown in figure 4. If we create the dataset with a chunk size of 10x1, each column of the dataset will be stored separately and contiguously. The read of a partial column can then be done is a single operation. This is illustrated in figure 5, and the code to implement a similar operation is shown in example 2. For simplicity, example 2 implements writing to this dataset instead of reading from it.

|

Example 2: Writing part of a column to a chunked dataset

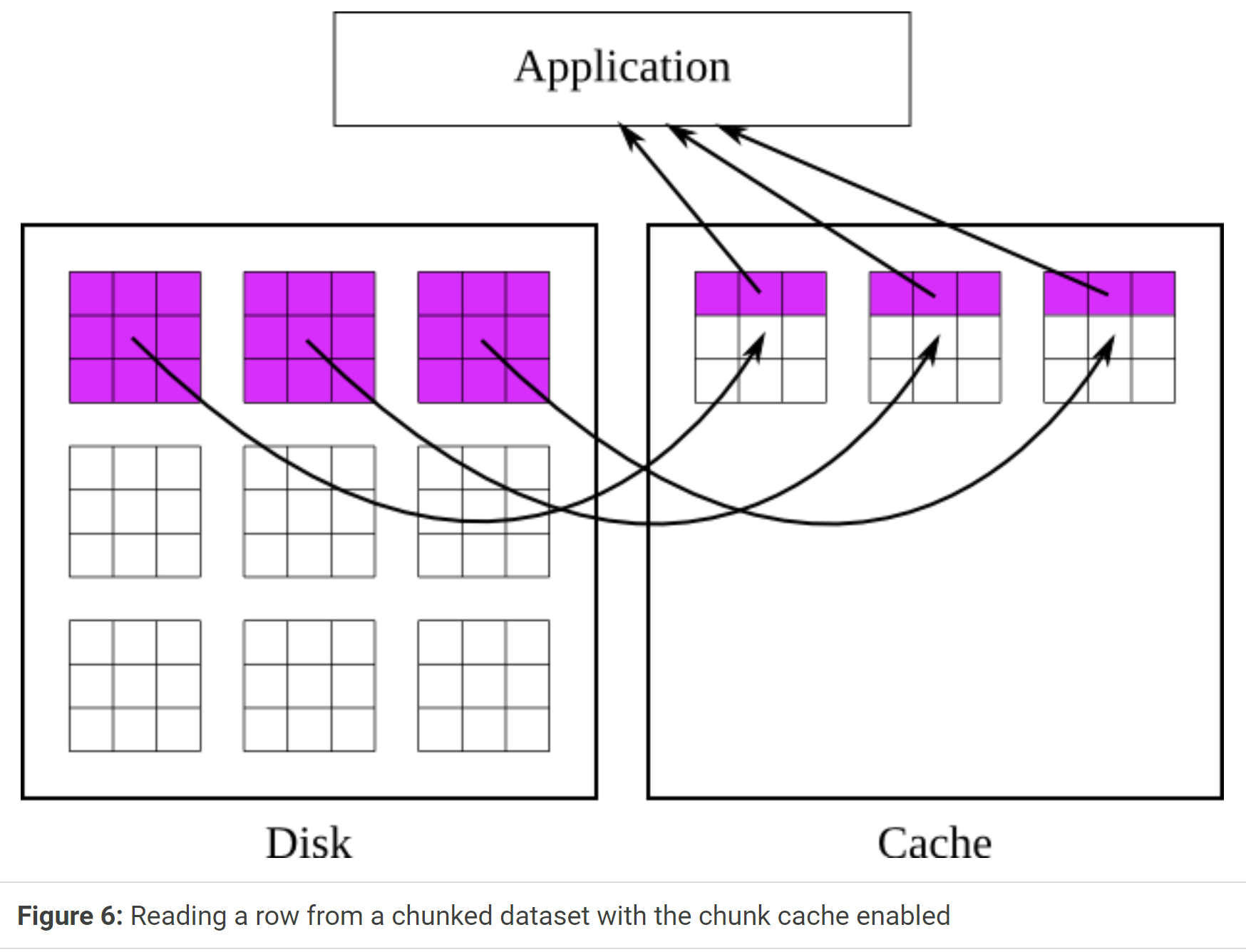

Another major feature of the dataset chunking scheme is the chunk cache. As it sounds, this is a cache of the chunks in the dataset. This cache can greatly improve performance whenever the same chunks are read from or written to multiple times, by preventing the library from having to read from and write to disk multiple times. However, the current implementation of the chunk cache does not adjust its parameters automatically, and therefore the parameters must be adjusted manually to achieve optimal performance. In some rare cases it may be best to completely disable the chunk caching scheme. Each open dataset has its own chunk cache, which is separate from the caches for all other open datasets.

When a selection is read from a chunked dataset, the chunks containing the selection are first read into the cache, and then the selected parts of those chunks are copied into the user's buffer. The cached chunks stay in the cache until they are evicted, which typically occurs because more space is needed in the cache for new chunks, but they can also be evicted if hash values collide (more on this later). Once the chunk is evicted it is written to disk if necessary and freed from memory.

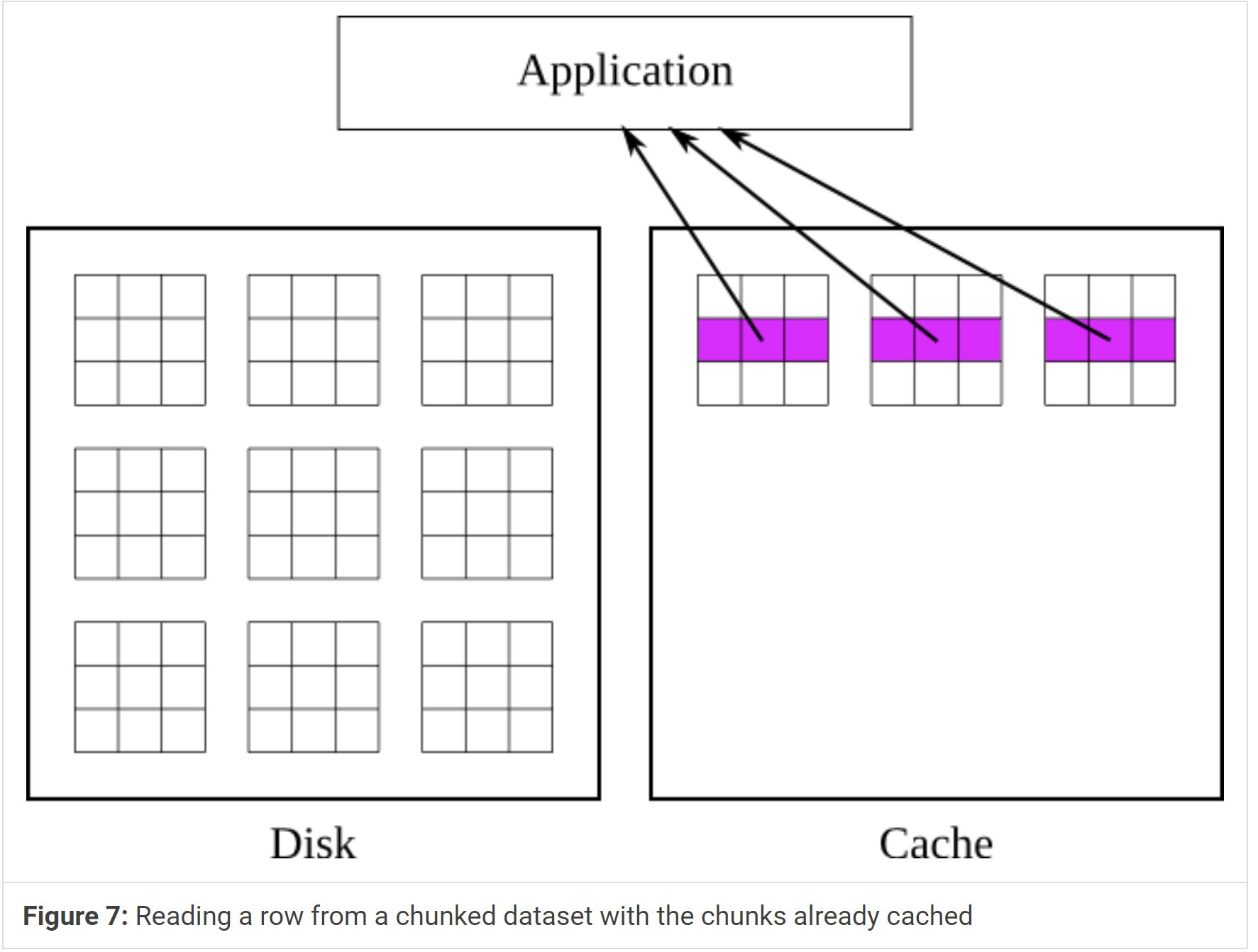

This process is illustrated in figures 6 and 7. In figure 6, the application requests a row of values, and the library responds by bringing the chunks containing that row into cache, and retrieving the values from cache. In figure 7, the application requests a different row that is covered by the same chunks, and the library retrieves the values directly from cache without touching the disk.

|

|

In order to allow the chunks to be looked up quickly in cache, each chunk is assigned a unique hash value that is used to look up the chunk. The cache contains a simple array of pointers to chunks, which is called a hash table. A chunk's hash value is simply the index into the hash table of the pointer to that chunk. While the pointer at this location might instead point to a different chunk or to nothing at all, no other locations in the hash table can contain a pointer to the chunk in question. Therefore, the library only has to check this one location in the hash table to tell if a chunk is in cache or not. This also means that if two or more chunks share the same hash value, then only one of those chunks can be in the cache at the same time. When a chunk is brought into cache and another chunk with the same hash value is already in cache, the second chunk must be evicted first. Therefore it is very important to make sure that the size of the hash table, also called the nslots parameter in H5Pset_cache and H5Pset_chunk_cache, is large enough to minimize the number of hash value collisions.

Prior to 1.10, the library determines the hash value for a chunk by assigning a unique index that is a linear index into a hypothetical array of chunks. That is, the upper-left chunk has an index of 0, the one to the right of that has an index of 1, and so on.

For example, the algorithm prior to 1.10 simply incremented the index by one along the fastest growing dimension. The diagram below illustrates the indices for a 5 x 3 chunk prior to HDF5 1.10:

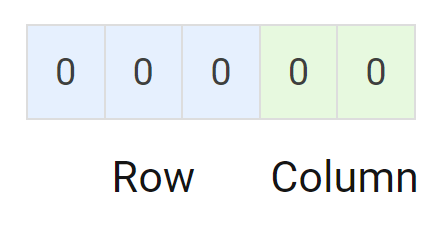

As of HDF5 1.10, the library uses a more complicated way to determine the chunk index. Each dimension gets a fixed number of bits for the number of chunks in that dimension. When creating the dataset, the library first determines the number of bits needed to encode the number of chunks in each dimension individually by using the log2 function. It then partitions the chunk index into bitfields, one for each dimension, where the size of each bitfield is as computed above. The fastest changing dimension is the least significant bit. To compute the chunk index for an individual chunk, for each dimension, the coordinates of that chunk in an array of chunks is placed into the corresponding bitfield. The 5 x 3 chunk example above needs 5 bits for its indices (as shown below, the 3 bits in blue are for the row, and the 2 bits in green are for the column)

5 bits |

Therefore, the indices for the 5 x 3 chunks become like this:

This index is then divided by the size of the hash table, nslots, and the remainder, or modulus, is the hash value. Because this scheme can result in regularly spaced indices being used frequently, it is important that nslots be a prime number to minimize the chance of collisions. In general, nslots should probably be set to a number approximately 100 times the number of chunks that can fit in nbytes bytes, unless memory is extremely limited. There is of course no advantage in setting nslots to a number larger than the total number of chunks in the dataset.

The w0 parameter affects how the library decides which chunk to evict when it needs room in the cache. If w0 is set to 0, then the library will always evict the least recently used chunk in cache. If w0 is set to 1, the library will always evict the least recently used chunk which has been fully read or written, and if none have been fully read or written, it will evict the least recently used chunk. If w0 is between 0 and 1, the behavior will be a blend of the two. Therefore, if the application will access the same data more than once, w0 should be set closer to 0, and if the application does not, w0 should be set closer to 1.

It is important to remember that chunk caching will only give a benefit when reading or writing the same chunk more than once. If, for example, an application is reading an entire dataset, with only whole chunks selected for each operation, then chunk caching will not help performance, and it may be preferable to completely disable the chunk cache in order to save memory. It may also be advantageous to disable the chunk cache when writing small amounts to many different chunks, if memory is not large enough to hold all those chunks in cache at once.

Dataset chunking also enables the use of I/O filters, including compression. The filters are applied to each chunk individually, and the entire chunk is processed at once. The filter must be applied every time the chunk is loaded into cache, and every time the chunk is flushed to disk. These facts all make choosing the proper settings for the chunk cache and chunk size even more critical for the performance of filtered datasets.

Because the entire chunk must be filtered every time disk I/O occurs, it is no longer a viable option to disable the chunk cache when writing small amounts of data to many different chunks. To achieve acceptable performance, it is critical to minimize the chance that a chunk will be flushed from cache before it is completely read or written. This can be done by increasing the size of the chunk cache, adjusting the size of the chunks, or adjusting I/O patterns.

Chunks have some maximum limits. They are:

For more information, see the entry for H5Pset_chunk in the HDF5 Reference Manual.

Inappropriate chunk size and cache settings can dramatically reduce performance. There are a number of ways this can happen. Some of the more common issues include:

Luckily, because each slot in the hash table only occupies the size of the pointer for the system, usually 4 or 8 bytes, there is little reason to keep nslots small. Again, a general rule is that nslots should be set to a prime number at least 100 times the number of chunks that can fit in nbytes, or simply set to the number of chunks in the dataset.

The slide set Chunking in HDF5 (PDF), a tutorial from HDF and HDF-EOS Workshop XIII (2009) provides additional HDF5 chunking use cases and examples.

The page Examples Description lists many code examples that are regularly tested with the HDF5 library. Several illustrate the use of chunking in HDF5, particularly Datasets and Filters.

Dataset Chunking Issues provides additional information regarding chunking that has not yet been incorporated into this document.

As seen above, the HDF5 chunk cache currently requires careful control of the parameters in order to achieve optimal performance. In the future, we plan to improve the chunk cache to be more foolproof in many ways, and deliver acceptable performance in most cases even when no thought is given to the chunking parameters.

One way to make the chunk cache more user-friendly is to automatically resize the chunk cache as needed for each operation. The cache should be able to detect when the cache should be skipped or when it needs to be enlarged based on the pattern of I/O operations. At a minimum, it should be able to detect when the cache would severely hurt performance for a single operation and disable the cache for that operation. This would of course be optional.

Another way is to allow chaining of entries in the hash table. This would make the hash table size much less of an issue, as chunks could share the same hash value by making a linked list.

Finally, it may even be desirable to set some reasonable default chunk size based on the dataset size and possibly some other information on the intended access pattern. This would probably be a high-level routine.

Other features planned for chunking include new index methods (besides b-trees), disabling filters for chunks that are partially over the edge of a dataset, only storing the used portions of these edge chunks, and allowing multiple reader processes to read the same dataset as a single writer process writes to it.

Navigate back: Main / HDF5 User Guide / Additional Resources